Me in front of former Catholic Church in Licheng, Jinan, Shandong, China in 1982, in use as a warehouse

In February 1982, I got an opportunity I never imagined would come, after ten years of studying China from afar—a chance to visit for a prolonged period, a chance to get to know some ordinary Chinese people, and to break down barriers to mutual understanding. I hurriedly finished my Ph.D. thesis at Stanford, a study of the motivations of Chinese for participating in the Communist revolution. Being a student wasn’t making me thrive; I was so financially desperate that I had to leave as soon as possible to start earning fellowship income, to barely keep my head above the water. So, I left for Beijing just before Chinese lunar year. It surprised my hosts at Shandong University because they expected me to wait until the holiday was over.

In front of dormitory and the “company car” of Shandong University, February 1982

Chilling Out (literally) in Beijing, PRC

I had to wait in Beijing for a week to let the school prepare for my arrival on campus. My program hosts put me up in a Beijing “hutong” just to the east of the Forbidden City. A hutong is a small alleyway, leading to a converted compound of an old Chinese family, with an open courtyard in the middle. I imagined how multiple generations and branches of family members used to gather in this place. The room had a soft bed with fluffy pillow, a wicker chair, and a private bathroom. It was comfortable enough, but in the bitter cold of the windy Beijing winter, it was a hardship to venture out of the room. It did have some heat, and I adopted the Chinese practice of constantly drinking hot water in thermoses, the only way to keep warmth inside my chest.

Nice room in hutong, but no warm enclosed lobby

During the day, I struck out to take photographs of Beijing. I had a camera with wide angle and long-distance lenses which could take quality photos, but it attracted too much attention. It was almost impossible to take pictures of people, except from a distance. As soon as people spotted me they would hide. I did visit the top tourist attractions in the city, primarily the former Imperial Palace (forbidden city) which was surrounded by stone walls and an iced-over moat.

On thin ice

Moat of the forbidden city, Beijing

Moat of the forbidden city, Beijing

TianAnMen Square, Beijing

Unfortunately, my young 30-year-old body could not stand up to the windy sub-freezing weather. I caught a bad cold that bordered on pneumonia. I holed up in the hutong hotel with Tylenol, a bottle of Scotch, and a copy of Norman Mailer’s Executioners Song, the story of the crimes and execution of the killer Gary Gilmore in Utah. Reading that 600+ page book helped keep me occupied in my room, and despite futile self-medicating with the bottle, my severe cold didn’t kill me, although it also didn’t get much better.

(My reading material while sick)

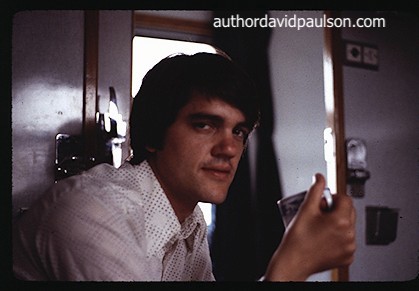

Arriving in Jinan City, Shandong Province, PRC

After about a week I got permission to travel by train over 200 miles down to Jinan, Shandong. It was still during the extended Chinese New Year’s holiday period, so when I arrived, a man from the university foreign management office showed me to my dormitory room, and appointed someone to check in with me every few days. The room was heated a little bit, but I still slept wearing long underwear, blue jeans, and a heavy padded overcoat. The dorm had a filthy unheated shower room, with just a trickle of hot water. The way to cope was to quickly disrobe and enter the shower, apply some soap, rinse off, and then towel off before the cold got you shivering.

It was a hardship for me, but I was quite aware that compared to the Chinese I was living in luxury. Later I observed that a whole Chinese family of three generations might be stuffed in a few rooms, with the toilet being a trench outside where the whole community would line up to shit or piss in the morning. For the Chinese, a bath or shower was a weekly event, and you could see women and girls cycling back from the baths in the cold, their hair still wet. These Chinese were living much closer to nature than we were, even compared to when we were camping.

(My dorm room at Shandong University, a bed, a small table, a couch, a mirror and a bookcase. Quite adequate although the heat was almost non-existent)

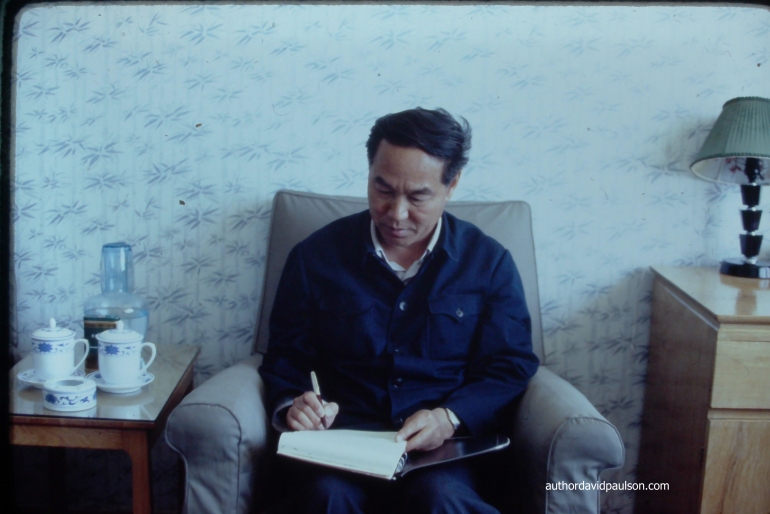

Yu Hua, The Dynamo of the Foreign Office

The foreign office was headed by a 40’ish woman named Yu Hua. Yu Hua was about 5’ 4” tall, stockily built, with a pretty face even without makeup, which no Chinese woman used. I told her that my cold was severe. Yu Hua was a capable person who was exceptional because she actually took initiative and did some work instead of sitting around “studying” all day like everyone else in her office. It was like this because everyone got paid the same pittance no matter what they did, and worse than in an American union shop, there was a disincentive to take any initiative or take any responsibility. I perceived that others respected her, and maybe also feared her. Anyway, she found a doctor who prescribed Chinese herbal medicine, a sticky black ball of vegetable material the size of a small fist, that supposedly could do something to remedy a cold. Chewing and swallowing this awful paste had absolutely no effect on my symptoms, but I was young and eventually recovered without the help of antibiotics.

Yu Hua at work managing the foreign community

Against my better judgement, upon arrival, I was very eager to explore the city of Jinan and take photos. I needed some transportation. Yu Hua took me and some of the other foreigners on an expedition in the government taxi to the “Friendship Store” where I could buy items not available to the Chinese populace in exchange for hard dollars. Jinan had a hidden room on the second floor of a building that could only be entered with special permission. There I bought a clunky, black, one-speed bicycle. The country was so poor that ordinary citizens had to “apply” to buy a bicycle, and they were not accessible to purchase in the normal market. The only other thing the store had worth buying were some blankets and a candy called “White Rabbit”. Even that candy was a luxury, since there were no restaurants to eat in in the city and only the crudest foodstuffs were sold. Anyway, I made my purchase and started riding around the city, wearing a heavy padded coat and carrying a small backpack with a camera in it, trying to take photos without attracting attention, a difficult task because I stuck out immediately due to my blue jeans, leather shoes, and foreign face.

My bicycle, this photo is from the summer, much better

Jinan Tourist Attractions

Jinan, a middle-sized industrial city, did have a few tourist attractions. One was the train station built of stone by the Germans during the 1920’s or 30’s, which of course was still intact without change because after 1949 there we no investors to fix up any buildings.

Jinan train station, built by Germans

Another was a large lake in the center of the city, Daming-hu, surrounded by charming (damaged and inactive) temples.

Someone fell under the ice in DaMingHu lake, and they sent a boat out to retrieve them

DaMing lake, downtown Jinan

A third was the Leaping Spring which was dried up due to a drop in the water tables.

Leaping spring

Finally, about two miles from the outskirts of the city there was the Yellow River bridge. Later I observed that sometimes brown water flowed in the river with a strong current, and at other times it was a dried-up surface that one could wade across easily.

The Yellow River bridge, just outside Jinan, when water was high

Yellow River when water was high

New Years Celebrations

It being New Years, I observed temples decorated with hand-painted lanterns, for the “lantern festival”. It was a relief to see a little wit and artistry. The climax of the public New Year’s celebration was a parade of stilt-walkers and lion dancers. Each factory unit contributed trucks to carry their workers around, dressed in holiday costumes, and it was funny to see that many of the workers were dressed in drag. One man with a doleful face was costumed in a western wedding dress.

stilt brigade of construction company

Stilt walkers at New Years in Western wedding dress

Deplorable Public Morality

One thing you learn if you study China is that the government was traditionally considered to be a remote entity, for better or worse. The emperor sat high and far away. Even now, some Chinese people, even those living in the US, boast that they have more freedom in China than in America, although personally I would discount that view. In the US from elementary school on, we are admonished to follow rules that promote mutual respect of others in public. Of course, now we are carrying it too far with extreme political correctness. To many foreigners coming to the US, e.g. from the Middle East or South America, this civility used to be perceived as one of the strong points of our society. At least we have some rules for public behavior, whereas in the older world the rulers act with impunity, and people are cruel to each other in public.

You have to experience it to believe it. Try lining up at the post office or a bus in China – there was no line, just a mob scene. Littering and spitting on the street was pervasive. I observed people sticking their heads outside bus windows, holding one nostril with a finger, and blowing snot out the other nostril onto the street. People were rude to each other, pushing in crowds, and there was no concept of customer service. Even in elite hotel restaurants like in the Beijing Hotel, waiters would openly show their contempt for the guests, sometimes just refusing to serve them. The only compensation is that if Chinese people actually met you, they would suddenly treat you as a dear friend. It was one or the other.

Civility and politeness month on campus

Clean up campaign on campus of Shandong University

Use a handkerchief please, sir!

One child policy

A little exercise–Chinese know how to exercise without sweating

Chinese Curious About Foreigners But Still Reserved, Except For Farmers Who Had Nothing to Lose

In pre-1949 China the populace pretty much went their own way, only complying with government demands in the limited situations where they had contact. That mentality survived to some extent after 1949, but the Chinese Communist regime was much more intrusive than any previous government. The regime divided the population up between the workers and poor and middle peasants on one side, and oppressors on the other—an artificial caste system. They also instituted a travel pass system which made it impossible for peasants to migrate to the cities to find a better life. It was a double caste system.

From 1949 up to the current time, the government stimulated envy and jealously between people and created spectacles called “struggle sessions” where “the masses” sought revenge for real or imagined grievances. Many people were humiliated or even beaten to death in mass spectacles. Obvious this was not a way to promote mutual respect. It was much harder to be “non-political” in the post-1949 society and not be affected by the policies of the government. But to some degree the mentality of distancing from authority still persisted, and some vestige of family feeling and individual friendship survived.

In 1982 the Chinese people I was interacting with still had a strong memory of leftist persecution and they were afraid to get too close to foreigners. They could open up a bit, but appearances were everything. If they didn’t manage the optics, and openly showed individual friendship with foreigners, it could potentially arouse jealousy. Anyone associating with foreigners was vulnerable. The only ones who could associate with us freely were the “foreign control office” led by Yu Hua, and the students of the three English teachers. I was not an English teacher, and my only contact there was with a history professor, some librarians, people introduced by the English teachers, and some arbitrary strangers I met when I was out riding my bicycle. I would make friends with one of the history professors, and got close to his son who I enjoyed hiking with, but he made great pains to avoid being associated with me publicly. I did him a favor by taking some nice color photos of his family, but I had to mail them to his wife’s work unit after the film was developed. I couldn’t send them to him directly at the history department.

After I left, in 1985, the government launched another campaign against “Spiritual Pollution”, and I hope that none of the people I befriended got in trouble. So, what I witnessed at New Year’s 1982 was that there was a tiny crack in the wall of conformity. A little bit of humanity was allowed to reveal itself during this most sacred national holiday.

Farmer friends of the English teachers, Jinan suburbs

Professor Chen and youngest daughter

Son of Professor Chen. Good hiking companion

Son of Professor Chen. Good hiking companion

Professor Chen from Shandong University History Department. What a natural pose!

Librarians downtown

Introducing the English Teachers and Foreign Students

Shortly after arriving at Shandong University I was introduced to two American English teachers, Joe and Romaine from Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania. Romaine was divorced and was scratching out a living as an ESL teacher, and Joe was in a similar desperate predicament. Back in the US they were struggling, but in China each got their own apartment with a kitchen and private bath, and they got a lot of respect from the faculty and the students. The students would seek them out to discuss personal matters, and they were in the best position to observe Chinese society and behavior. Some of their observations made me laugh. For example, the most popular students in their classes were the jocks – the best basketball players and the track stars. Very similar to the culture of an American high school.

Romaine and Joe, from Pennsylvania, English teachers

There was also a third English teacher, an academic in his 30’s who had failed to get tenure back in the US. It was a particularly hard for him to be there. He was lonely and piled up a huge mountain of brown liter-sized beer bottles in his apartment over the winter. It wasn’t until spring that he because less depressed, getting friendly with a visiting professor from the US. I was happy for him at that time, and he became more approachable, but before the visitor arrived he was too dour for me to relate to.

I also met a hodge-podge of non-American foreign students, three French, one Italian, one Brit, and one Japanese. Most of them were carrying their own plates and utensils to the dining room where we shared 3 meals a day. Their faces had a yellow pallor. The kitchen staff in the foreigner’s cafeteria had been careless, and served the foreign students contaminated food which gave them Hepatitis A. I admired the European students’ resilience in staying in China after getting sick. They could have gone home to seek a cure, but they chose to stick it out. I wonder where they are today, but have no way of finding them.

The European students, two French girls on left, one Japanese man, French ring leader, Phillipe, Italian man Giovanni, one Brit, and one more Japanese man who smoked all the time

Fortunately, the kitchen seemed to have cleaned up its act a bit before I arrived. I had got a gamma globulin shot back in California which gave limited immunity to Hepatitis A and B. After arriving in China, it was too late for the others to get shots. This was because when they gave injections in China they re-used the needles, a very unsafe practice, even in the years just before the HIV epidemic.

Some of my Stanford classmates who studied at other universities suffered from a variety of health problems that they joked about, like intestinal worms. Thank god, I was spared that affliction too. A few foreign students died from viral encephalitis, but none from my school.

The foreign students told me to be very careful what I ate, and to never try the (virtually non-existent) public restaurants in Jinan. We stuck with the school cafeteria, where our diet was actually better than the average Chinese. I think the Chinese had no rice, little meat, and their staple was a fist-sized white bread-like roll called the “mantou” along with fried vegetables like cucumbers. As a contrast, we students were served rice every day, and a little pork and starved chicken once in a while. The challenge with the rice was that the farmers separated the kernels from the chaff on cement, so it contained little black rocks that could break a tooth. We joked with the kitchen staff by picking the rocks out of the rice and returning them.

Open Street Markets (very limited)

preparing something. what?

Summer street market

Market open to allow people to sell food grown in their own small private plots

Bringing pig to small open market

Bringing pig to small open market

Cactus salesman

Turtle saleswoman

Home-made vermicelli

Best beard in town

Our farmer friend again

The local Whole Foods

Pitch fork anyone?

Korean War POW’s Who Elected to Stay in China

Within a few days of my arrival I met two more Americans in the compound. During the Korean War, after the US recovered from the North Korean surprise attack, General McArthur was on the verge of pushing the North Korean Army to the north out of Korea into China. The Chinese intervened with a massive infusion of 500,000 troops who overwhelmed the army of the United Nations and pushed it back to the 35th parallel (where the border is today), capturing about 7,000 Americans. At the time of the armistice in 1953 an exchange of prisoners was arranged between the UN forces and the Chinese. The prisoner exchange was controversial because many of the Chinese prisoners in hands of the UN forces didn’t want to return to China. As a propaganda counterattack the Chinese offered to let American prisoners stay on in China. At least 21 American soldiers accepted this arrangement, and for some reason two were living in Jinan now with us.

One of them, James Veneris, had an apartment in our compound. He had learned Chinese, and had a Chinese wife (his third), but he was still starved for English speaking company. He invited me to his apartment and we hit it off pretty well, since I understood the historical background of what happened to him, and was a little more mature and empathetic than the other students.

Jimmy also came from Pennsylvania, from a coal mining district. He was drafted into the army, and told me “there’s nothing worse than carrying a rifle and a rucksack.” The promises of Chinese socialism had appeal for him, even though he didn’t get a lot of schooling. His parents were still living in the US, but beyond that he had nothing to return to. When the Chinese offered him a job (in a toilet paper factory), and place to live, and even a wife, he was happy to accept the offer. He was not in good health by now, in his late 60’s, worn from too much smoking and drinking. The foreign students told me that the Chinese resented his special treatment a bit, seeing him as a loafer, but he did work and above all was still a true believer in Maoism.

(James Veneris, Korean War POW)

(In brown shirt, Howard Gayle Adams, Korean War POW)

I also met the other former POW, Howard Gayle Adams, who was better educated and seemed to have adapted better. He had a more sophisticated perspective on events in China, and had a sense of humor. He kept a low profile, never giving any interviews to the foreign press, and I didn’t get to know him well.

Feelings of Isolation

I’d drop in on Jimmy once in a while for tea, but frankly we didn’t have much in common, other than feelings of isolation. The feelings of isolation were the hardest thing to endure for students or other visitors to China. The Japanese students had it a little better, because they could camouflage themselves when they went out, and they were not immediately recognized as foreigners if they didn’t open their mouths. Japanese write with Chinese characters and they have a greater affinity for Chinese culture than Americans.

The students of American and European background could not blend in and disappear. Every time we walked outside the compound we were stared at. No one needed to be appointed to spy, because the whole population was spying on us.

I heard from my classmates in Beijing, that some foreign men started affairs with local Chinese women. This was a big taboo for the Chinese, and it would cause a lot of political trouble for both members of the couple. It was even worse for the African students, who were supposed to be 3rd world allies of the Communist regime. There were incidents in Beijing and other places where Chinese mobs attacked the dormitories of the African students, resenting their promiscuity, their drinking, or whatever it was. It wasn’t that bad in Jinan, maybe because there was little social mixing with the Chinese, except on the part of the English teachers, who weren’t doing any sexual mingling.

There was a lack of entertainments for us in Jinan. There was one TV set in the dormitory. The Chinese guards monopolized it to watch Peking Opera, so it was of little use to us. They showed some movies to the Chinese students in public places. I attended once, but the film was just propaganda, and it wasn’t worth it to me to watch.

I tried to come up with entertainment ideas for the “foreign student manager”. Yu Hua had access to a van, and she liked to take us on trips, maybe because she and her staff got to go themselves. One idea that I can claim credit for is the prison visit. I asked Yu Hua, “Can we visit the prison? There must be a prison here in Jinan.” In fact, there was a provincial prison in the city, close to the university. To my surprise, she liked the idea and arranged a school trip, which was a success and became a regular thing.

Visit to Provincial Prison

Wardens with the students

The prison rules: discipline, study, and sanitation

going in

Living quarters for the prisoners

In front of the prison gate

Shandong Provincial Prison

Yu Hua assembled the whole group of foreign students. I don’t think anyone declined to go. We drove a short distance to a massive walled prison compound. The warden met us at the gate, in uniform of course, and walked us through the barriers into the prison. The first thing we were struck by was the fact that the prison was the cleanest and most orderly place we had seen in China. The warden showed us a room where the prisoners lived. The straw mats on the store reminded me of tatami mats in Japanese houses, everything totally clean and in order. In China prisoners are given work, a taboo in the US where this is seen as “slave labor”, but in my view, it was not necessarily a bad idea. It gave the prisoners something useful and potentially fulfilling to do. Even Solzhenitsyn saw the therapeutic value of work in the Russian gulag. The Chinese prison had some large industrial machinery. I’m not sure what they were producing.

We asked the warden the obvious question: “Do you have any political prisoners in here?” His answer was simple and direct, “Of course we do.” I speculate that most of the prisoners were not there for political reasons. Jinan like any big city had a population of “thugs” and “toughs,” and some of the prisoners must have fit that category. North China is a rough-and-tumble place.

Of course, we couldn’t ask to interview the prisoners – that would out of the question, in China or any other country. Anyway, we got to take photos, and ironically, I think the students, the foreign student managers, and the wardens and guards all enjoyed it. It was a break in their boring routine.

Visiting the Birthplace of Confucius, Sacred Mountain Tai, and Scene of Novel Water Margin

Burial mound of Confucius. I walked over his head

Confucius Temple in Qufu

Approach to Confucius Temple

Casual dining near Qufu

These children are over 40 now

Rural scene in SouthWest Shandong

Dirt street in Southwest Shandong

Hmm, what happened to my stomach later?

Yu Hua and peonys

Yu Hua organized several other more conventional trips: Tai-shan (one of the sacred peaks of China), Liangshanpo (the setting of the Chinese novel about a bandit gang, called Water Margin), a visit to a Peony field in the South West, Chufu the birthplace of Confucius, and others.

When we visited a peony field in the South West, we took note that the villages there seemed particularly primitive, dirt roads, dirt walls, everything dirt, much poorer than the suburbs of Jinan. When the group, including the POW Jimmy, entered the peony field, the local people came out in a mob to watch the foreigners. Our managers got nervous. The crowd was restrained by a barb-wire fence around the garden. Suddenly the crowd burst through the barrier and came in to stand by us and look at us. It was pure curiosity on their part. Even something as simple as a pair of blue jeans or leather shoes were something for them to see. They didn’t do any harm other than embarrassing our “managers.” Our managers were embarrassed that the poverty in China was being revealed, but actually for the foreigners the scene was perceived as beautiful, and we were not perturbed by the poverty. We already knew about that, so no big deal, but the Chinese guides had the illusion that they could hide it from foreign eyes.

Local farmers staring at foreigners in Southwest Shandong peony field

The crowd broke in to stare at us

Foreigner posing with flowers

I enjoyed all these trips, and the best was the birthplace of Confucius. Confucius was an actual historical figure who lived in China over 2,000 years ago. Due to the Chinese “ancestor worship,” his lineage can be traced to the present. As of 1982 his main heir was living in Taiwan. During the Cultural Revolution, the students were encouraged by Mao to attack the “four olds,” smashing every relic of China’s ancient culture, whether it be in an urban area or in the countryside. They targeted Chufu but someone in the leadership protected it. So, the estate of the Confucius family was still intact, as a tourist attraction for a limited audience. As you approached the compound you traveled on a road with stone figures on each side, having been there for hundreds or thousands of years. The family supported a beautiful temple, and you could see Confucius’s actual grave, a huge mound. At this time, they actually let us walk on the mound, so I can say that I’ve climbed on the actual grave of Confucius. To me this was a very moving experience and I have photos. Now in 2019, I think the site has been restored a tourist attraction, and I doubt that anyone is allowed to get that close to the grave any more.

Hiking Around Jinan

Back in Jinan, as I said before, I made friends with one of the Chinese history professors, Professor Chen. I met his wife, his two daughters, and his son who was in his early 20’s. They were born before the “one child” policy went into effect. Professor Chen was a very honest man. We discussed nothing political. I just admired his work ethic and his character. I enjoyed going hiking in the mountains around Jinan with his son. The mountains nearby are steep but no rock climbing is required. They can be climbed to the top with a vigorous hike.

Mountain just on outskirts of Jinan

Itinerant bee keepers from Southern China

Shocking Damage Caused by Rampaging Red Guards during “Cultural Revolution” of 1965

To the North of Jinan, the mountains included some Buddhist temples and cave carvings that were over 1,000 years old. Maybe they have been restored for tourism by now. However, when I was there, I got to see how they were desecrated by the Red Guards. For example, they drilled holes in the heads of the of the Buddha’s and tried to explode them with dynamite. All the buildings were damaged and slogans from the Cultural Revolution were scratched everywhere, like graffiti in New York of the 1970’s. Also, we found a gravesite of a historical figure from the Republican Period, and it was desecrated, broken, with a pool of dirty water on top. Reminiscent of what is happening now in the US with the attacks on Confederate statues. Even little temples high up on mountains were desecrated. The government gave the students free rein to attack people and create chaos, and in the end, they had to rely on the military to put a stop to the anarchy and violence.

Red Guard destruction of monuments over 1000 years old

Protest grafitti demanding restoration of damaged temple

Defaced grave of KMT soldier

Trashed Buddhist statue, over 1000 years old

Tunnels Built to Prepare for Nuclear War with the USSR

The most shocking thing to see was the tunnel system that Mao ordered built after the dispute with the USSR became bitter. As I said before, the Chinese feared that the USSR would attack them with nuclear weapons, and they built huge tunnels under various cities, Jinan being one of them. The openings in the mountain caves were large enough for big military equipment to drive in. Just think how many resources were dedicated to this nonsense when the population was living at the edge of subsistence. And what good would these defenses have been in the face of a nuclear attack? You can’t stuff over 1 billion people into a few tunnels.

China still has over 3,000 miles of tunnels built for “nuclear defense”

Later we learned that the Russians asked President Nixon and Henry Kissinger if they would mind if Russian nuked China. Nixon warned Russia not to do that, so in fact he may have actually prevented it from happening.

Historical Research Trip to Mountains of South Shandong and the Jiaodong Peninsula

Outside of the general school trips, the school arranged a research trip for me with my professor. They got a taxi for me, and just before we set out, the driver turned on the meter, and I realized that they were going to charge me the urban rate for driving over 200 miles. I stopped the car and negotiated a day rate. Then we set out again. We traveled to the mountains of southern Shandong where the Communist movement got its start after the Japanese invasion of 1937. The Japanese invaders took control of the major cities and the railways between them, but didn’t penetrate far into the countryside. This created a vacuum that the Communist and Republican guerrilla filled. That’s why we went out to the mountainous area.

I think my professor got a lot more value out of this trip than me, since I had so many linguistic difficulties that I could barely understand anything. In Shandong they speak Mandarin Chinese, which was what I studied, but the rural people had heavy local accents. It’s like, if someone studies English in a posh part of London, and then visits rural people in North Carolina, do you think they would understand much? Another frustrating thing was, the Chinese would speak very frankly among themselves, but I could only catch part of it. The leader of the Communist movement in Shandong during WWII, Li Yu, was purged after the war ended, and a lot of local people were murdered by the secret police chief Kang Sheng. I could hear the professors and interviewees quietly opine that the policies of the time were “too extreme” (guo huo), but I could not capture any of the details. A third factor was that the events described in my thesis took place almost 40 years previously, and each person only had a partial view of the events, so what value was their testimony anyway? The material I collected during this visit was almost worthless, but at least I got to see the physical scene.

Reminiscing about WWII in South Shandong mountains

Reminiscing about WWII on Jiaodong Peninsula

Qingdao

Qingdao beer, originally German, available in your local Chinese restaurant

Qingdao Brewery

Shandong Under Japanese Occupation, 1937-1945

By the time I left China, I felt that my research had reached a dead end. The information I collected was too fragmented. The setting was too alien. And none of the documentary evidence I collected could be traced back to acts of individuals. It was impossible to construct an interesting narrative. In the Communist movement, only the very top leaders like Mao or Zhou Enlai are allowed to have personalities. I decided that I had to make a big change in my life.

Wartime leaders, military leader Luo Ronghuan 7th from left, party leader Li Yu 1st on left, Xiao Hua 5th from left. 3rd from left is Liu Shao-qi, the primary target of the Cultural Revolution in the mid 1960’s.

wartime militia

Guerrilla Leader Li Yu addressing the troops

Too Bad, No Do-Overs

Subsequently I have thought about how I would research my subject if I could do it over again. I think the only way to do it is to find some documentary evidence so you have a structure to pin the observations to, and focus on maybe 5-10 key informants, hear their stories in great detail with a digital recorder, work with a translator to get the nuance even if you have studied the subject language, and then use the material to create a group narrative. The best example I have seen is Barbara Demick, Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea. I bow to her, and if I had it to do over again, I would try to follow her process, but unfortunately in life there are very few do-overs.

Actually after I left the field, one more foreigner attempted to write the same story, and then finally a Chinese insider took up the task, Sherman Xiaogang Lai, A Springboard to Victory: Shandong Province and Chinese Communist Military and Financial Strength, 1937-1945, published in 2011. I uncovered part of the materials contained in this book, but was unable to understand the context. It took a native speaker of Chinese with connections within the Chinese military to pull that off.

Visiting Mao’s Childhood Home in Changsha, Hunan

In August 1982, I left China, having made a few Chinese friends, but on the whole feeling defeated. I traveled by train down to Hunan with all my research notebooks and books. I visited Mao’s home village. It was swelteringly hot, that’s all I remember.

Portrait of Mao Zedong, and his son, probably Mao Anying, who died in the Korean war victim of an American air strike

Parents of Mao

Mao’s childhood home. He threatened to jump into the pond to commit suicide to spite his father

Good Books on China, no Bullshit

When I crossed the border to Hong Kong, again I felt great relief to be in a free atmosphere. And I knew I couldn’t devote more time to this research, this exercise in futility. A year later I left the China field, taking an entry-level job in IT in New York, and turned my back on over ten years of training in Chinese language, history and culture. I was disappointed that I couldn’t find satisfying work in the China field, but I’m also happy that I never have to read another bad book about China. I have a low appetite for propaganda and historical distortion.

If the reader really wants to understand China, I would refer them to four writers who are still active, Frank Dikotter, author of The Tragedy of Liberation, Jasper Becker, author of Hungry Ghosts, journalist Peter Hessler, author of River Town and Strange Stones, and Hans van de Ven, author of China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China. The latter draws on some of the research that my professor Lyman Van Slyke and my classmate Chen Yung-fa conducted on the Chinese revolution. My own work is not mentioned—too limited in scope, too trivial, too lacking in context.

These are all astute observers, having good feel for Chinese culture and history. and are not afraid to speak the truth. Historical narrative is largely shaped by the victors, but in the USA we still live in a free society and we can be sympathetic to China without swallowing the official Chinese narrative whole. If the reader doubts what I am saying, look what’s happening in Hong Kong right now in 2019. Those protestors are Chinese, not foreigners, and they aren’t too happy with the historical outcome, to say the least. Let’s hope that their voices can continue to be heard.

Enjoyed your story

LikeLike